In Korea, 22 Labor and Civil Society Organizations Held Press Briefing on “Problems and Policy Alternatives in the Draft Enforcement Decree and Other Subordinate Regulations of the AI Framework Act”

"What Will Happen When the AI Framework Act Takes Effect in January 2026?"

- Digital Rights, Education, Labor, Culture, Healthcare, and Consumer Groups Express Concerns

"Subordinate regulations that broadly exempt high-risk operators from responsibilities leave people's safety and human rights exposed to AI-related risks"

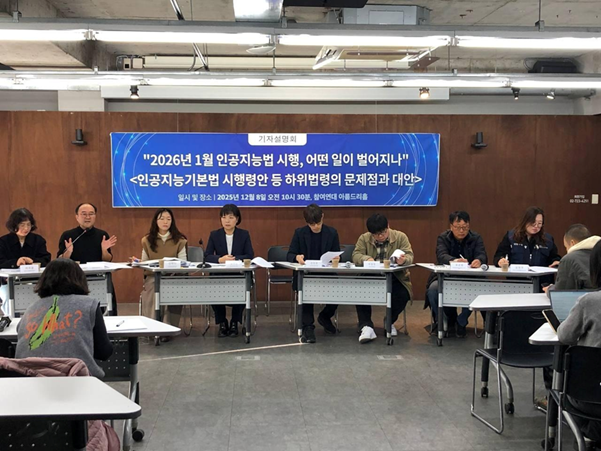

1. On Monday, December 8, 2025, at 10:30 AM, 22 labor and civil society organizations held a press briefing at PSPD’s the Areumdri Hall in Seoul to criticize the problems in the government's proposed Enforcement Decree and other subordinate regulations for the "Act on the Promotion of Artificial Intelligence Development and the Establishment of a Trust-Based Environment" (hereinafter, the 'AI Framework Act') and to call for policy alternatives from civil society. Digital rights, education, labor, culture, healthcare, and consumer groups unanimously pointed out that the subordinate regulations, which broadly exempt high-risk operators from their responsibilities, risk leaving affected people’s safety and human rights exposed to the dangers of AI.

2. The subordinate regulations for the AI Framework Act, which was promulgated on January 23, 2024, and is scheduled to take effect on January 22, 2026—namely, the draft Enforcement Decree, draft Notices, and draft Guidelines—were released on September 17. Among these, the draft enforcement decree underwent partial clause revisions on November 13 and is currently undergoing a legislative notice period to collect public comments until December 23. The AI Framework Act has faced criticism from civil society for several reasons: ▲ it contains no provisions prohibiting AI systems that influence a person’s subconscious or exploit vulnerabilities such as age or disability to induce certain behaviors; ▲ the scope of “high-impact AI operators” is narrowly defined; ▲ the obligations imposed on high-impact AI operators are insufficient, and even when violations occur, administrative fines are imposed only if the operator fails to comply with a corrective order from the Ministry of Science and ICT, raising doubts about the Act’s effectiveness; ▲ it includes no provisions on the rights or remedies of individuals affected by AI; and ▲ it broadly excludes AI used for national defense or national security purposes from the Act’s application. Given these limitations in the AI Framework Act's provisions for preventing AI-related risks, the subordinate regulations must supplement measures to protect people's safety and fundamental rights. However, the current drafts often fail to specify the concrete protective measures delegated by the law. Worse still, they add multiple grace periods concerning business operators' responsibilities that are not stipulated in the Act itself.

3. Oh Byoung-il, president of the Digital Justice Network, pointed out that although the law delegated the authority to designate additional categories of high-impact AI to the enforcement decree, the draft decree contained no provisions on this matter. As a result, AI systems that pose risks to people’s safety and human rights—such as facial recognition in public spaces and emotion recognition in workplaces and schools—fall into regulatory blind spots. He particularly criticized the draft for classifying certain businesses deploying AI for operational purposes—such as hospitals, recruitment firms, and financial institutions—as mere 'users', thereby entirely exempting them from the responsibilities of “operators” (e.g., risk management, explainability, and human oversight). Businesses that actually deploy AI systems, such as news providers or video producers, were also classified as “users”, thereby being exempted from the obligation to label deepfake content. He argued that AI business operators deploying AI for business purposes and directly affecting individuals through their systems should bear appropriate responsibilities as “AI operators”.

4. Kim Ha-na, Chairperson of the Digital Information Committee of MINBYUN(Lawyers for a Democratic Society), pointed out that the draft enforcement decree failed to specify key responsibilities for high-impact AI operators, with many such matters appearing only as non-binding recommendations in public notices or guidelines. She emphasized that important matters delegated by law, and those directly affecting people's rights and obligations, must be stipulated in the enforcement decree. Furthermore, she raised concerns that the draft enforcement decree, by exempting certain fact-finding investigations not authorized by law and allowing an unspecified extended grace period, may exceed its delegated authority. She further criticized this approach as prioritizing corporate interests over people’s safety and the protection of human rights, even in cases where AI products and services cause safety incidents or human rights violations.

5. Meanwhile, voices from various sectors raised concerns about problems found in the draft subordinate regulations. Kim Hyun-joo, the Director of Steady Call Center Branch of KPTU(Korean Public Service and Transport Workers' Union), highlighted that contact center workers are already suffering serious harm from AI deployment, including layoffs, surveillance, responsibility gaps, and customer safety risks. She criticized the lack of legal mechanisms to protect call center workers and customers affected by AI, emphasizing the urgent need to establish such protections.

6. Following this, Choi Sun-jung, Director of Institute for True Education and Spokesperson of KTU(Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union), expressed concern that the government's AI talent development policy subordinates education to industrial demands, weakening the rights of students and teachers and the public nature of education. He called for a policy shift towards cultivating critical AI citizens capable of addressing the ethical challenges posed by technology.

7. Furthermore, Ha Jang-ho, the Policy Committee Chair of Cultural Action, pointed out that government policies overly focused on promoting the AI industry have resulted in a serious lack of public discussion and policy responses to the severe threats to livelihood, labor rights violations, and the potential collapse of the social and cultural foundations in the cultural and artistic sectors.

8. Jeon Jin-han, the Policy Director of Korean Federation of Medical Groups for Health Rights, also expressed concern that insufficiently validated AI systems are being indiscriminately deployed in healthcare settings, leading to serious risks such as misdiagnoses, safety hazards, and unjustified medical billing. He criticized that, despite these dangers, the AI Framework Act fails to regulate such practices, effectively leaving the medical field as a regulation-free zone.

9. Finally, Jeong Ji-yeon, the Secretary General of Consumers union of Korea, expressed concern that the introduction of AI has caused consumers to experience inconvenience when forced to interact with chatbots and has infringed upon their right to human contact. She pointed out that when AI-related harm occurs, consumers are effectively left to bear the burden of proof. She stressed the urgent need for safeguards to protect socially vulnerable groups and institutionalize consumers’ right to participation.

10. As building a growth-oriented 'AI powerhouse' is the Lee Jae-myung administration's top national priority, protecting the rights of those affected by AI-related risks is even more crucial. Korean Civil society has consistently emphasized that preparing for the dangers AI poses to people's lives, safety, fundamental rights, and democracy is the state's duty, while proposing policy alternatives. Following today's(December 8th) press briefing, civil society submitted its initial opinion statement on the subordinate legislation for the AI Framework Act, including the draft enforcement decree, draft notices, and draft guidelines. Civil society opinion statements for specific sectors such as labor, education, culture and arts, healthcare, and consumers will continue to be submitted in the future. / End /

▣ Press Briefing Overview

- Title: "What Will Happen When the AI Framework Act Takes Effect in January 2026?" - Press Briefing on <Problems and Policy Alternatives in the Draft Enforcement Decree and Other Subordinate Regulations of the AI Framework Act>

- Date & Location: December 8, 2025, 10:30 AM / PSPD's Areumduri Hall

- Co-hosted by: Digital Information Committee of MINBYUN, Digital Justice Network, Institute for Digital Rights, PSPD, KPTU, Headquarters of the Movement to Stop Healthcare Privatisation and Achieve Free Healthcare, Cultural Action, Media Christian Solidarity, The Democratic Legal Studies Association, Korean Federation of Medical Groups for Health Rights (Korean Nurses association for Health Rights, Korean Pharmacists for Democratic Society, Korean Dentists Association for Healthy Society, Solidarity for Worker's Health, Association of Physicians for Humanism, Doctors of Korean Medicine for Health Rights), Civil Society Organizations in Korea, Citizen's Mediation Center Seoul YMCA, Policy Committee of People's Coalition for Media Reform, Human Rights Education ONDA, KTU, KMWU, KCTU, Solidarity for Child Rights Movement ‘Jieum’, Joint Committee for Freedom of Expression and Against Media Repression, Consumers Union of Korea, WomensLink, Korean Women's Federation for Consumer (22 organizations listed above)

- Program

-

- Moderator: Lee Ji-eun, Senior Staff Member, Public Interest Law Center, PSPD

- Core Issues of the Subordinate Legislation draft (1): Oh Byoung-il, President, Digital Justice Network

- Key Issues in the Draft Subordinate Legislation (2): Kim Ha-na, Chairperson, Digital Information Committee, MINBYUN

- Sector-Specific Problems and Proposals in the Draft Subordinate Legislation

- Labor: Kim Hyun-joo, Branch Director, Steady Call Center Branch, KPTU

- Education: Choi Sun-jung, Director of Institute for True Education and Spokesperson of KTU

- Culture and Arts: Ha Jang-ho, Policy Committee Chair, Cultural Action

- Healthcare: Jeon Jin-han, Policy Director, Korean Federation of Medical Groups for Health Rights

- Consumers: Jeong Ji-yeon, Secretary General, Consumers union of Korea

▣ Attachment (Korean)

- Civil Society Opinion Statement on the Draft Enforcement Decree

- Civil Society Opinion Statement on the Public Notice and Guidelines

- Press Briefing Statement

▣ Key Points of Civil Society's Opinion Statement on the Draft Enforcement Decree

We reiterate that the draft enforcement decree must be revised and supplemented to reflect the following recommendations.

- First, while Korea's AI Framework Act recognizes the rights of individuals affected by AI, the draft enforcement decree includes no measures to protect or remedy those rights. It also fails to provide concrete mechanisms enabling affected individuals to exercise their right to request explanations. Furthermore, regarding the responsibilities of high-impact AI operators, it merely specifies measures to protect users—essentially, the businesses utilizing AI systems—rather than the affected individuals themselves. The Ministry of Science and ICT must stipulate effective measures in the draft enforcement decree to ensure the protection and remedy of the rights of affected individuals.

- Second, unlike the EU's AI Act, Korea's AI Framework Act does not prohibit AI systems with significant potential for human rights violations, such as facial recognition in public spaces, the exploitation of vulnerabilities, and emotion recognition in workplaces and schools. Therefore, at the very least, the definition and responsibility provisions for high-impact AI in the enforcement decree should sufficiently address AI systems posing risks to safety and human rights and specify the measures required to address them. Nevertheless, the draft enforcement decree contains no provisions whatsoever, even for matters explicitly delegated to it under the law concerning high-impact AI.

- Third, the draft enforcement decree narrowly interprets “use operators” inconsistently with the legal provisions, treating all businesses using AI products or services for operational purposes as mere “users” and thereby exempting them from all responsibilities. Consequently, businesses using AI for operational purposes—such as hospitals, recruitment firms, and financial institutions—are not required to fulfill responsibilities like risk management, explainability, or human oversight toward affected individuals like patients, job applicants, or loan applicants. Unlike users who "use the provided product or service as-is without altering its form or content," businesses such as hospitals, recruitment firms, and financial institutions that use AI "for business purposes" and directly affect individuals should bear appropriate responsibilities as “use operators”.

- Fourth, the draft enforcement decree exempts parties actually using AI systems—such as news businesses or video producers—from the obligation to label deepfake content. AI operators that do not actually produce deepfakes cannot reasonably be expected to bear this labeling duty. Therefore, to resolve this issue, it is necessary to include businesses utilizing AI systems as “use operators” and impose appropriate responsibilities upon them.

- Fifth, the AI Framework Act broadly excludes AI developed or used solely for national defense or national security purposes from its scope of application, based solely on designation by the Director of the National Intelligence Service, the Minister of National Defense, or the Commissioner General of the National Police Agency. As no legislation to regulate AI for defense or national security purposes is currently being pursued, this raises concerns about a regulatory vacuum for AI systems that poses the severe risks of human rights violations. Nevertheless, the draft enforcement decree broadly defines fields such as “national security core technologies” as “AI developed and used solely for defense or national security purposes”. To prevent AI with dual-use potential from being secretly developed and operated under the national defense or national security purpose exception, thus evading the minimum obligations set forth under the Act, the National AI Committee should at least be mandated to deliberate and decide which AI systems are exempt from application.

- Sixth, the draft Enforcement Decree sets an extremely narrow threshold for defining “frontier AI” subject to safety obligations, establishing it as AI models whose cumulative compute used for training is 10 to the power of 26 FLOPs or more. Furthermore, beyond this technical requirement, it must also meet criteria announced by the Ministry of Science and ICT considering AI technological advancement levels and risk factors, making the scope even more restrictive. Few, if any, AI systems currently meet this criterion. Even if the threshold is revised in the future in line with technological progress, it should be set at 10 to the power of 25 or higher so that current major frontier AI systems are adequately encompassed. Additionally, obligated operators should be required to disclose key information about their risk management systems and frameworks.

- Seventh, regarding the responsibilities of high-impact operators, the draft Enforcement Decree stipulates that they "shall comply" (Article 34, Paragraph 1 of the Act), while the Notice merely states that "compliance may be recommended" (Article 34, Paragraph 2 of the Act). The legal status of the Enforcement Decree, Notice, and guidelines is distinct. For matters that are merely recommendations, especially those involving costly measures, it is difficult for operators to comply, and sanctions for violations become nearly impossible to enforce. Nevertheless, the draft enforcement decree often omits crucial matters that should be explicitly stated, leaving them only in notices or guidelines. Particularly for important matters delegated by law and those directly affecting people's rights and obligations, they must be stipulated in the enforcement decree. Therefore, the key contents of notices and guidelines regarding the responsibilities of high-impact AI operators should be regulated by the enforcement decree.

- Eighth, the draft enforcement decree stipulates exemptions from fact-finding investigations not delegated by law and allows for the operation of a substantial (unspecified) grace period. This policy effectively signals that even if safety incidents or human rights violations occur due to AI products or services, the state will forgo minimal administrative investigations or, in practice, refrain from imposing administrative fines. Since companies have repeatedly raised complaints regarding fact-finding investigations and administrative fines, it is questionable whether exempting or deferring these measures prioritizes corporate grievances over people’s safety and human rights protection. This overall regulatory design effectively signals, at a national level, that AI products and services may be released to the market without fulfilling essential obligations—such as providing explanations to consumers and other affected individuals, ensuring human oversight and supervision, or preparing and maintaining required documentation—thereby failing to safeguard those impacted by AI, at least for the foreseeable future.

To ensure that Korea’s AI Framework Act—now drawing global attention— genuinely protects people affected by AI-related risks and achieves a human rights–based approach consistent with international human rights norms, civil society submits the following comments on the draft Enforcement Decree and urges the government to incorporate them in full.

▣ Key Points of Civil Society's Opinion on the Notice and Guidelines

We recommend the following improvements.

- First, regarding the draft Safety Assurance Notice and AI Safety Assurance Guidelines, we proposed that since these documents do not apply to all AI systems, they should be clearly specified as applying to Advanced AI - for instance, as the Advanced AI Safety Assurance Notice. We also pointed out that by targeting specific AI systems, the guidelines create ambiguity about whether AI model providers are subject to compliance, make it difficult to manage the inherent risks of AI models, and fail to clarify who determines whether an entity is subject to obligations. Furthermore, as previously noted in our opinion on the draft enforcement decree, we reiterated that the notice and guidelines define the scope of entities subject to safety assurance obligations too narrowly. In addition, we emphasized the need for the Ministry of Science and ICT to list obligated operators and require them to disclose key information about their risk management systems and frameworks.

- Second, Regarding the draft Notification on Obligations of High-Impact AI Providers and the accompanying Guidelines, we pointed out that the duties of AI developers and AI use operators may differ, yet the distinction between these roles is vague and arbitrary. This issue is also connected to the draft Enforcement Decree, which defines businesses using AI systems for operational purposes as “users”. The failure to define the rights of affected individuals and the responsibilities of users (or use operators) is a major problem. The draft Guidelines on Obligations of High-Impact AI Providers lack specificity compared to the Safety Assurance Guidelines and require substantial revision.

- Third, regarding the draft AI Transparency Assurance Guidelines, the AI Framework Act imposes obligations on AI developers and use operators. It explicitly states that entities that only use AI products/services to generate outputs for their own services do not qualify as businesses under the Act and therefore bear no transparency assurance obligations. Consequently, entities such as news organizations (e.g., YTN) or video producers that create content using generative AI technology have no labeling obligations. Furthermore, businesses providing generative AI services are only required to offer labeling functionality, leaving no entity actually responsible for fulfilling labeling obligations. Even if a business is explicitly designated as a user, if it takes the initiative in developing and providing its own AI-based services, it should be regulated as an AI use operator rather than a mere “user”.

- Fourth, regarding the draft High-Impact AI Determination Guidelines, there is an overall tendency to arbitrarily narrow the interpretation of the listed categories of high-impact AI systems, contrary to the intent of the text, or to minimize their scope by imposing additional restrictive requirements. This risks violating higher-level laws and is also undesirable from the perspective of protecting fundamental rights.

- Fifth, regarding the draft AI Impact Assessment Guidelines, we recommended several improvements: renaming the document as a “Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment”; establishing requirements to ensure the independence and expertise of the assessment body; providing for cooperation with the National Human Rights Commission of Korea; reviewing the preparedness of the assessment team during the preliminary planning stage; emphasizing the need to understand relevant stakeholders and the broader social context in which the AI system is used; explicitly requiring consultation with affected individuals as an essential procedure; and ensuring that the assessment does not restrict the scope of fundamental rights considered to civil and political liberties only.

/ End /